17. VI–15. X 2023

Tartu Art Museum

Artists: Georg Goob, Jane Grier, Johann Knopf, Joseph Alois Gottlieb Maier, Anna Marie Lieb, Michael Kolb, Anonymous author (Case 240), Stefanie Richards, Baroness Zerheimb, Alois Dallmayr, Heinrich Mebes, August Natterer, Emilie Wulffius, Günther Heinrichsohn, Anonymous author, Mait Rebane, Heiki Säga, John Lake

Curators: Mari Vallikivi, Eva Laantee Reintamm

“You must watch the trains.”

“But if someone asks you why you’re going to see them, what do you say?”

“I tell them I’m checking out the train. All the way to the end. Here in Imastu.”

“How far is the end?”

“From here to the very end! I’m checking out that train.”

“What will you do when it’s gone?”

“Then I’ll head to Tapa. To see the train. In the depot.”

“Do you want to drive it too?”

“Yes.”

“What if you could drive anywhere you wanted?”

“Elva.”

“Why Elva?”

“Towards Elva. A long way.”

“But when you get to Elva, what will you do?”

“Then the locomotive will stop.”

“And when it stops, what then?”

“What do you mean?”

“When it stops, what will you do?”

“Then I’ll step off the locomotive.”

“So where are you going?”

“Home!”

“I see! Do you know where home is?”

“In the village of Tamsa.”

“Have you been to Tamsa?”

“I have.”

“When did you go?”

“Last year!”

“Really!?”

“Yes!”

“What did you see there?”

“I saw my mother.”

“Oh! And what did Mum say?”

“Mum says: “Hi, Valdek! How’s life?” And I tell her, “Life is very good!””

“But didn’t she ask where you’re living?”

“She did ask!”

“And what did you tell her?”

“Mum asked me, “Valdek, how’s life? How’s your sleep?””

“And your response?”

“I slept well and I lived well.”

“But she didn’t suggest you come back home for good?”

“What?”

“Didn’t she say you should come back home and not be so far away?”

“I live in Imastu!”

“But your mother didn’t invite you home?”

“Well, Mom could come over. By train. The cars are connected. To the locomotive. These cars.”

“What else did you do at home?”

“I watered the flowers.”

*

This conversation has stayed with me ever since I first watched the documentary “Winter of the Ladybug”1 (Lepatriinutalv, 1989, directed by Hagi Šein and Hille Tarto). In fact, I’m not sure you can remain unchanged after seeing this film. Witnessing human vulnerability, fragility and profound, delicate beauty – these layers of stone peel away, revealing more beneath.

The documentary unveils life in the Imastu and Karula boarding schools for disabled children and youth during the 1980s. Fearlessly and sensitively captured by the late, legendary Dorian Supin (1948–2023), the camera portrays children crawling, making sounds and gently swaying, their heads shaved. Abandoned children. A considerable number of them struggle with speech and mobility. Hagi Šeini manages to engage with some of them. Among them is Valdek, a teenager who shyly smiles when answering the filmmakers’ questions. His face glistens, perhaps due to anxiety or the formal attire he wears for the camera.

Valdek, once a reserved 10-year-old, was brought by his mother to the Imastu boarding school. They came by train, from Elva. Valdek’s mother, an “ordinary, unpretentious woman”, seemed like the type who would visit her son periodically. he assured the caregivers that Valdek would be home for the summer. The summers passed, and as several years went by, Valdek’s letters to his mother remained unanswered. His anticipation-filled days were filled with drawings of trains – hundreds and hundreds of them. Occasionally, he’d even attempt to stop real trains with his makeshift wand.

Valdek’s memory lingered in my mind. For some reason, it was important for me to know he was okay. That thirty years on, he’s surviving and managing. I embarked on a search for Valdek and discovered his traces – two drawings – in the Kondas Centre art collection. Valdek still draws trains, but the destination is no longer “ELVA”. The brightly coloured trains now bear inscriptions like “ELEKTRIRAUDTEE”, “EDELARAUDTEE”, “GO RAIL” and “RAIL BALTIC”.

Five years ago, Valdek’s drawings graced the Kondas Centre’s “Collected Worlds” exhibition, also curated by Mari Vallikivi. Valdek was described as the exhibitor of the most impactful pieces, having “dwelt in a world of trains since childhood”.2

A few years after the documentary, aged 23, Valdek participated in the 1995 Paralympics in the United States, representing Estonia in bowling. Described by Connecticut’s prominent newspaper, The Hartford Courant, as initially shy and reserved, Valdek transformed into a community’s heart and soul upon receiving an affectionate American welcome.3 Paralympians, embraced as heroes, found camaraderie on foreign soil, waved at by strangers on the street eager to have a word with them. Locals offered Valdek hospitality and taught him some English. One can only imagine what this meant for him. The newspaper described how, in a Somersville pizzeria, over spaghetti, Valdek momentarily escaped the “dismal institution” that constituted his daily life.

Despite everything, it seemed life held Valdek in its embrace, carrying him onward. I had found Valdek and was ready to leave it at that – until I learned about an exhibition featuring work from the Prinzhorn and Kondas Centre collections at the Tartu Art Museum. I didn’t come across Valdek’s train drawings, but in a way, I encountered him – or myself? – in an unexpectedly intimate manner.

*

Art lovers in Estonia will be familiar with some of the artists in the Prinzhorn collection thanks to the “May You Be Loved and Protected” exhibition, curated by Tamara Luuk at the Tallinn Art Hall a few years ago (17. X–20. XII 2020).4 However, this time, the original pieces from this rare collection will be on display for the first time in Estonia. The Tartu Art Museum’s exhibition aims to spotlight a pivotal period in the early 20th-century history of psychiatry and art, underscoring the historical ties between Tartu and Heidelberg. Heidelberg’s Prinzhorn Museum houses one of the largest art collections (with around 6,000 pieces in the historical section) created by psychiatric patients before the advent of modern psychopharmacological drugs. Alongside historical works, contemporary “outsider art” from our Kondas Centre collection will be exhibited.

It has been suggested that only the German psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933), proficient in both domains, succeeded in expanding aesthetics to encompass “art produced in the context of insanity”.5 His 1922 publication “Artistry of the Mentally Ill” (Bildnerei der Geisteskranken) marked the initial endeavour to comprehend the creative output of psychiatric patients not only psychologically but also aesthetically. The book gained instant fame and continues to be influential.

Mesmerised by the boundary between psychopathology and artistic expression, Prinzhorn sought the underlying universal humanity, transcending cultural facades. He saw acts of creation, whether by Rembrandt or a mentally afflicted individual, as equally valuable expressions of the psyche. Prinzhorn took his stance even further by deliberately abstaining from using the word “art” in his book. Instead, he embraced the archaic German word Bildnerei – a term for “image creation”. This wasn’t due to it being unsuitable for the creations of psychiatric patients, but rather because of the implicit value judgments inherent in the term “art”. In essence, “art” distinguishes one form of creation from another, leading to similar creations being either recognised as “art” or disregarded as “non-art”.6 It’s based on the assumption that a norm exists to which deviations can be compared. Prinzhorn’s viewpoint differed: he believed that the act of creating images couldn’t be categorised as healthy or sick. It was a fundamental human drive for self-expression – an attempt to forge connections and bridge gaps with others.

Prinzhorn himself was no stranger to mental health problems. He grappled with depression, aggravated by the trauma of World War I, in which he served as a military surgeon. Prinzhorn described himself as an “unstable psychopath with hysterical tendencies,” an outsider hovering between heaven and earth, a man without a sense of belonging.7 The rigidity of Heidelberg University profoundly affected him, resulting in the loss of his teaching position. Nevertheless, he was known as someone skilled in harmonising diverse faculties, disciplines and individuals.8 Although Prinzhorn viewed the creators of his collection as genuine masters, he wrestled with great uncertainty and hesitation, doubting both his own value and that of his collection. His wife Erna, whom he had assisted in overcoming mental health struggles at the start of their relationship, now found herself supporting him as he sank deeper into depression. Their roles had reversed.

In the broader context, we mustn’t forget the world in which Prinzhorn and the artists he uncovered lived.9 The recently concluded World War I had torn through the joy of the Belle Époque, while the optimism of the Industrial Revolution had waned with the realisation that the constructive potential of human-made machines equalled their destructive capabilities. German streets were filled with injured men missing limbs. Naturally, the war left artists deeply affected; most emerged from it changed, if not physically, then mentally.

The significance and purpose of art became questionable. In response to the chaotic and bewildering world, the anti-war insurgent movement of Dada emerged, particularly popular in Germany. Dadaists condemned rationalism and logic as the primary culprits of devastating wars.10 In this context, insanity appeared to be the most fitting response. On the one hand, Expressionist theories that circulated in the early 20th century helped prompt psychiatric acknowledgement of art created in mental institutions. On the other, Prinzhorn’s collection subsequently influenced avant-garde artistic movements. It’s worth noting that both these influences were represented in Nazi Germany’s travelling exhibition of “degenerate art”, known as “Entartete Kunst” (1937–1941).

*

“His sister dies”; “he is widowed twice”; “he endures the loss of his children”; “at age 12, he is taken in by strangers, feeling miserable”; “friends and family convince him to marry, but the marriage is unhappy from the start”; “he often mentions triplets, sometimes four children he says he once had”. These descriptions offer a glimpse into the lives of the artists featured in the Prinzhorn Collection. The narratives, accompanied by more or less serious diagnoses, are showcased at the Tartu Art Museum. All those trains that never reach their destinations.

Numerous subjects can only be aptly expressed through the language of art. Oliver Sacks, the British neuroscientist, essayist and thinker, suggests that while horizontal connections with people, society and culture might fade, potent and profound vertical connections remain – direct links with nature, with a reality unaltered by influences, intermediaries or obscurities. He then poses the question: “[I]s there any “place” in the world for a man who is like an island, who cannot be acculturated, made part of the main? Can “the main” accommodate, make room for, the singular? [—] Is there some “place” for him in the world which will employ his autonomy, but leave it intact?”11

Valdur Mikita’s response resonates: most often, outsiders are exiled into care and kindness originating from our world, with little effort to comprehend the unique completeness and spiritual contentment of their world, which they fervently pursue, much like the rest of humanity.12 While standing before her paintings during the “Collected Worlds” exhibition at the Kondas Centre, artist Merike Sild declared her happiness: “Love makes you happy. I love to draw.”13 That’s all she said.

A similar feeling of happiness embraced me upon encountering the initial works at the Tartu Art Museum. As I continued through the exhibition, a distinctive, radiant sense of joy enveloped me. Could this be pure inspiration? Something every artist – every human – craves.

Speaking of gender, while over half of the patients in German mental hospitals were women, less than 20% of the pictures received by Prinzhorn belonged to women.14 This discrepancy reflects the societal status of women at the time. However, the exhibition at the Tartu Art Museum showcases the works of several prominent female artists from the Prinzhorn collection. Among them is Anna Marie Lieb, who created astonishing daily installations by tearing up linen, clothes, blankets and towels to form intricate patterns and shapes on the wardrobe floor, emanating an unusual clarity and structural harmony – a world of complete order.

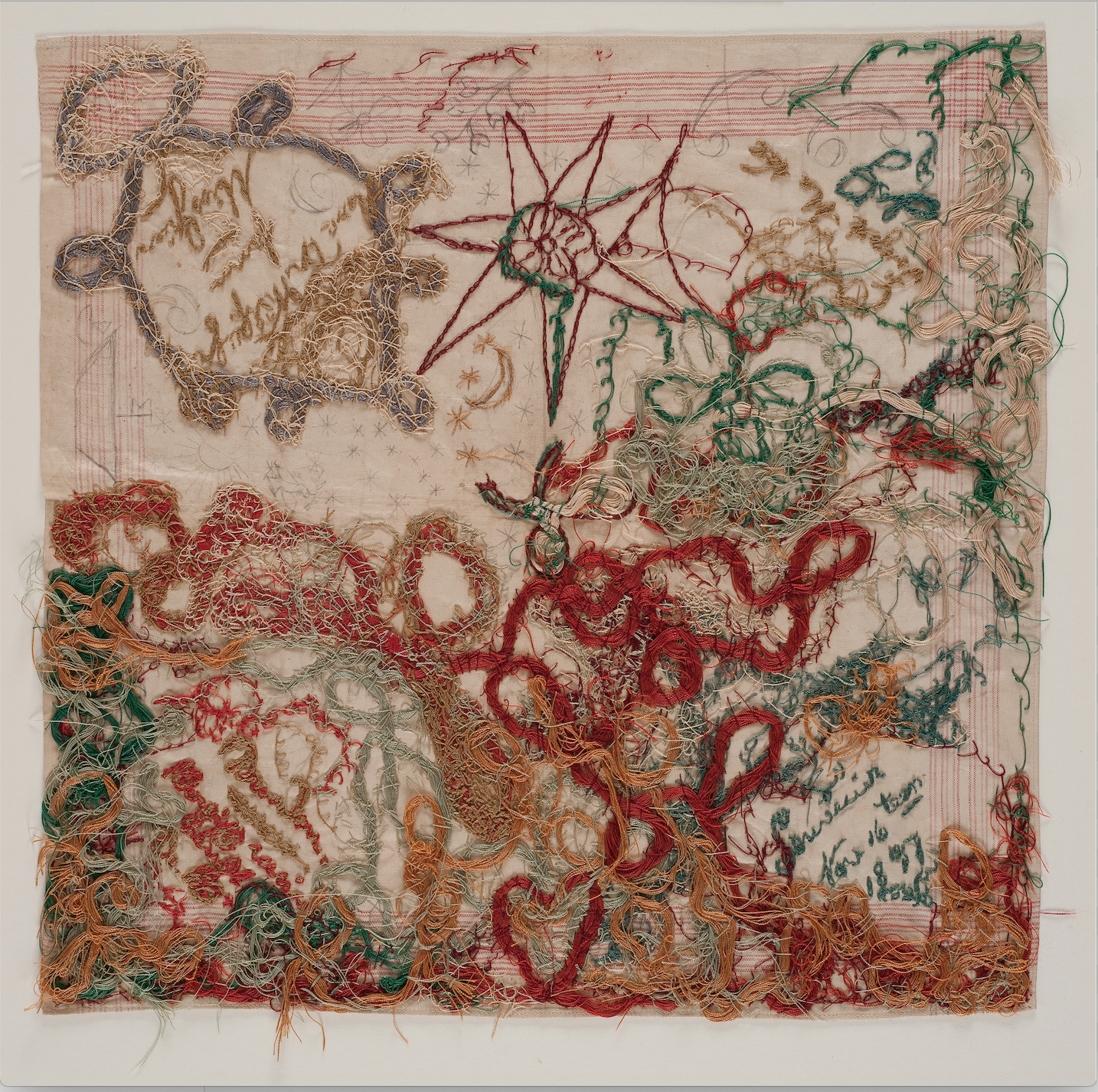

Jane Grier or Miss G (1856–1902)

Untitled

1897

embroidered handkerchief

Prinzhorn Collection

The patient’s case history unveils Lieb’s approach: she constructs her installations “with remarkable skill and determination, taking immense pride in her work and only dismantling it after a few days.” When facing psychiatric specialists, she confidently carries a self-made cane, describing her mental state as a “divine struggle”.

The short biographies and case histories on the walls of the Tartu Art Museum are almost as captivating and evocative as the artworks themselves. Take Joseph Alois Gottlieb Maier, who is noted to have created “beautiful drawings” during his apprenticeship as a shoemaker. While in the clinic, he writes art reviews and articles on contemporary political matters and sets up a shoemaker’s workshop. A talented comedian, juggler, and magician, he claims to have invented an airship in 1907 and completes it 1913, escaping the mental hospital “to defend his rights and interests related to his invention.”

The exhibition showcases boundless creativity and vitality that manifest in various forms and on diverse surfaces – be it a hospital floor, a handkerchief or a label on a morphine bottle. The Tartu Art Museum’s exhibition is equally accommodating and receptive to its visitors, accepting them exactly as they are (or are not).

Perhaps Mikita is onto something when he posits that in outsider art, “the notion of spiritual redemption, eroded by modernism, has discovered a sanctuary. In its pursuit to restore art to a magical ritual, outsider art thrives on its inability to fully grasp the essence of art. Art is life – it’s one and the same.”15

*

“Now I’m heading home for the summer, taking this train. It’s a pleasant journey. By train.”

“This very train?”

“Yes.”

“But where do you plan to sit? In the first car or the back?”

“In one of the rail cars.”

“Perhaps sitting here would be more thrilling? This spot offers a view as well.”

“There’s a motor in here. Inside the locomotive. An electric locomotive. It runs along electric lines. On the railway. Where there are no barriers. And where there are barriers.”

“Have you ever halted a train?”

“Never.”

“But you have this… wand?”

“Yes!”

“And if the train driver spots you, could they stop the train?”

1 See: https://arhiiv.err.ee/video/vaata/lepatriinutalv.

2 Tiina Sarv, Kui sõnade asemel kõnelevad värvid. – Postimees 26. VI 2018.

3 With Support, Memories, Estonians Leave Somers. – The Hartfort Courant 30. VI 1995.

4 See also: Hanno Soans, Defying gravity. – KUNST.EE 2020, no 4, pp 2–11.

5 John M. MacGregor, The Discovery of the Art of the Insane. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989, p 193.

6 Ibid., p 196.

7 Charlie English, Gallery of Miracles and Madness: Insanity, Modernism and Hitler’s War on Art. New York: Random House, 2021.

8 John M. MacGregor, The Discovery of the Art of the Insane, p 194.

9 Many thanks to Heie Marie Treier for an inspiring and context-expanding conversation.

10 Jonathan Jones, The first world war in German art: Otto Dix’s first-hand visions of horror. – The Guardian 14. V 2014.

11 Oliver Sacks, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales. New York: Harper and Row, 1987, p 231.

12 Valdur Mikita, Mõtestatud isolatsioon. – Solvates meduusi: modernismist lähtuvad rahvakunstid ja eesti külageeniused. Tigude süü. Ed. Sigrid Saarep. Tallinn: Tallinna Kunstihoone Fond: Kaasaegse Rahvakunsti Keskus, 2009, p 66.

13 Tiina Sarv, Kui sõnade asemel kõnelevad värvid.

14 Charlie English, Gallery of Miracles and Madness: Insanity, Modernism and Hitler’s War on Art.

15 Valdur Mikita, Mõtestatud isolatsioon, p 66.

Hedi Rosma is the Estonian editor of KUNST.EE.