“What are those bundles you’re carrying here, what’s that?

The new Kunst.ee? You’re the editor, yes?

In my day, I too produced a magazine.

Edited it myself, carried it myself, and then praised myself.”

– Leonhard Lapin

When the Republic of Estonia was born on 24 February 1918, art circles wanted, broadly speaking, three things: first, an art hall for staging new exhibitions; second, an art museum for educating future generations; and third, a specialist magazine for art criticism.

The fastest to materialise was the Art Museum of Estonia. Its charter was drawn up even before the Treaty of Tartu was signed on 2 February 1920. In other words, the War of Independence was not yet officially over, but the Estonians had already chartered their national art museum in 1919. Soon, lacking a building of its own, it moved into Kadriorg Palace – “temporarily”, of course.

Tallinn Art Hall took the longest. The modern functionalist building was ceremoniously opened to the public in 1934. As we know, five years later, the Second World War broke out. Barely a week before that, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was signed, its secret protocols spelling out exactly which territories the Soviet Union coveted in Eastern Europe.

Somewhere in between these events – half-slipping into obscurity – came the birth of Estonia’s first art magazine. Taie, an “Estonian art magazine”, as the cover proudly declared, was a periodical whose first issue appeared in 1928. A year later, four issues had been published, the last as a thick double issue.

And that was that. The production funding from the Cultural Endowment of Estonia had run out. Still, one cannot say the creators lacked foresight. On the cover of the debut issue, Günther Reindorff drew a phoenix – the mythical creature that burns to ashes and rises again, dies and is reborn.

*

In 2025, this Estonian art and visual culture quarterly celebrates its 25th birthday. The first quarter of the 21st century in the restored Republic of Estonia has been its era and context – the social backdrop against which it has taken shape.

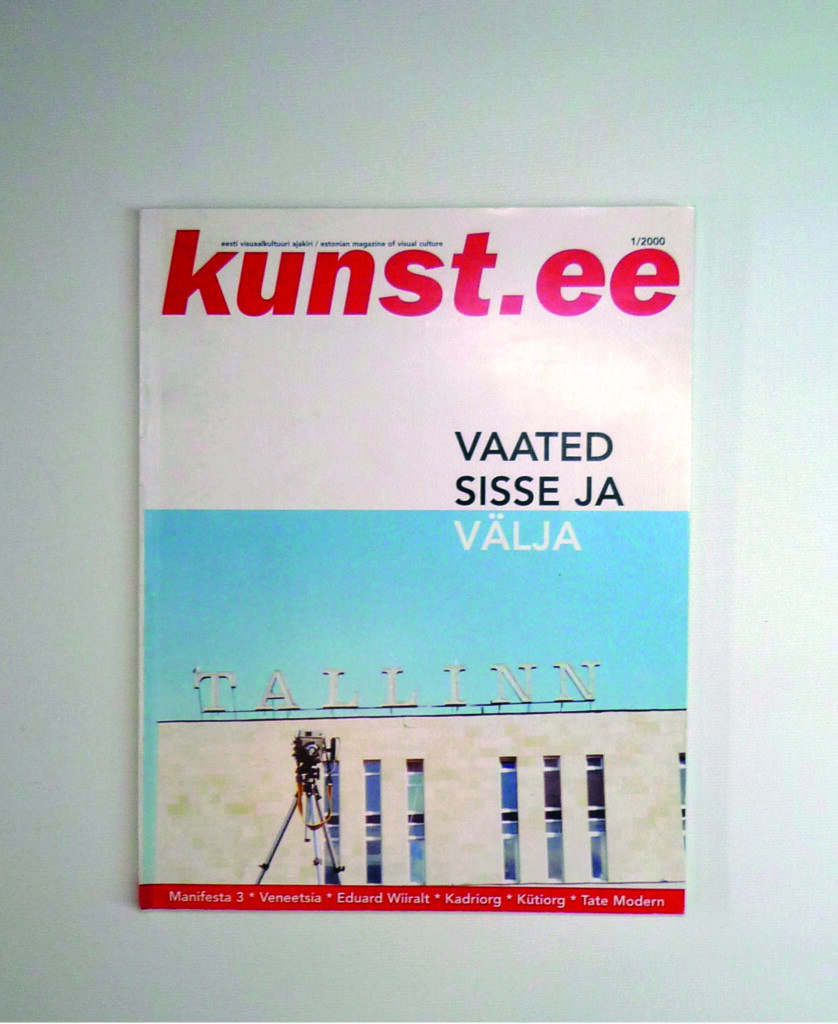

In November 2000, a pilot issue (1/2000) appeared, followed the next year by a regular publication cycle: a new, nearly 100-page issue every three months. Each year would therefore bring four issues (spring in March, summer in June, autumn in September and winter in December). This was the clockwork rhythm set in motion a quarter of a century ago.

No art periodical in Estonia had ever been published quarterly in the 20th century, but that does not mean the magazine emerged from nothing in 2000. Anyone who has glanced at the masthead of a recent issue will have noticed that, next to the subscription details and editorial contacts, it references the year 1958. So our story began a long time ago – in fact, even earlier than that, as hinted above.

Is it OK if, on this anniversary for Kunst.ee, I sketch the story in broad strokes? I promise to keep it brief.

*

Kunst.ee considers itself the successor to the almanac Kunst. Published between 1958 and 1996, Kunst was the flagship of the publisher Kunst – in terms not of print run but of image and symbolic weight. Had there been no art almanac, there would have been no reason to found such a publishing house in the first place. For many years, Kunst was the only publishing house in the country dedicated to visual art, enjoying what was effectively a domestic monopoly.

The window for creating such a centralised sectoral publisher opened in 1957. Stalin’s death brought a gradual softening of the previous politics of fear across the Soviet Union, and occupied Estonia was no exception. Crucial to advancing the publishing initiative was the support of the leadership of the republic’s artists’ union. After obtaining the approval of the Council of Ministers – the equivalent of today’s government – the founders travelled to Moscow to seek permission from the all-Union artists’ union, where they also met no resistance.

The name first proposed for the new publishing house was Taie. However, because it inevitably recalled the pre-war magazine edited by Märt Laarman (who had been expelled in absentia from the artists’ union in 1951 at the height of Stalinist repression), it was deemed unsuitable. Next came the more declarative Eesti Kunst (Estonian Art), but in the end, the longer, more official-sounding ENSV Kunst (Art of ESSR or the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic) was adopted. Later, it was shortened simply to Kunst (Art).

Reportedly, the publisher’s net profit for the first year reached one million roubles. The best-selling items were colour postcards, which became a scarce commodity in the austere post-war years. Of course, Kunst also published monographs, albums and, from 1958, the almanac Kunst, but the profit came mainly from elsewhere. Another major earner was Kunst ja Kodu (Art and Home), a high-circulation home-design almanac later given a Russian-language version for the all-Union market.

Although the Soviet planned economy typically favoured huge print runs, Kunst always hovered at just a few thousand copies. The lesson – that a narrowly focused specialist art magazine aimed at artists and art-interested readers might not be particularly profitable – had, in fact, already been learned in pre-war Estonia.

The first editor-in-chief of Kunst was Milvi Kartna (Alas). Among Soviet decision-makers in both Tallinn and Moscow, a trivial personal detail may well have inspired additional confidence: she was married to Arnold Alas, then head of the republican artists’ union. The fact that Estonians could both internalise the ruling power’s chauvinistic ideology and walk the tightrope when necessary is illustrated by how smoothly both the publisher and the almanac were ultimately established. In Leningrad, a similar initiative by the local artists’ union was reportedly shut down and silenced, or, in the parlance of the time, “archived”.

In fact, the most notorious censorship incident in the history of Kunst came under its second editor-in-chief. When Sirje Helme took over in 1975, she began inviting more ideas from the young and angry avant-garde. One could say, trouble was not long in coming. In 1979, Kunst (issue 55/1) published the image of Kazymyr Malevich’s black square. Designed by Leonhard Lapin, the cover bore a black square and the back cover a red one. Inside was an article on Malevich that infuriated the authorities. A planned companion piece never appeared. The editor-in-chief narrowly kept her post, but the radical designer was dismissed. The “reactionary” publication was reportedly criticised in a major political speech by none other than the first secretary of the Estonian Communist Party, Karl Vaino himself.

By 1996 however, when the final issue of Kunst (1/1996) was published, few still remembered Karl Vaino’s name – the world had changed beyond recognition. Communist rhetoric had given way to capitalist evangelism: as one popular weekly, Eesti Ekspress, proclaimed, even a paperboy could become a millionaire. The publisher Kunst, reorganised as a joint-stock company, tried to find its footing in a book market with shrinking print runs. Yet in hindsight, one cannot say its story ended happily or that it swam in money and opportunity. By the mid-1990s, Kunst was being assembled collectively, with the role of editor rotating among art historians and critics. One of those rotating editors was Heie Marie Treier.

*

In journalism, continuity matters. A pause of a couple of years in a print publication’s schedule is one thing; a pause measured in decades is something else entirely. In the latter case, you cannot speak of continuity – at best, you can speak of a historical predecessor, as with Taie. And although the media landscape of the 1990s was buzzing, with plenty of work for sharp-penned art writers, artists and art historians almost immediately began petitioning the state to revive the almanac Kunst.

On the initiative of Jaan Elken, then president of the Estonian Artists’ Association, one serious meeting was held at the Ministry of Culture in 1999, where Heie Treier, representing the Estonian section of AICA (the International Association of Art Critics), presented a concept for the revived publication. It was agreed that the new periodical would appear quarterly (rather than twice a year) and that a single managing editor would be hired (the previous rotating system had not proved workable). The Cultural Endowment of Estonia stepped in to fund the pilot issue in full, while the Estonian Artists’ Association provided the editorial office as an in-kind sponsor. All that remained was to settle on a name.

Alas, it soon became clear that the revived publication could not appear under the old almanac’s title, which still legally belonged to the joint-stock company Kunst. The new quarterly therefore needed a name that referenced Kunst yet differed from it by at least three characters. Heie Treier solved this seemingly impossible task by asking the scandal-courting poet Sven Kivisildnik – then working in advertising – to come up with a pageful of possible names. The chosen name, kunst.ee, was used exactly as is by designer Tõnu Kaalep when laying out the magazine. After the premiere issue appeared, publishing duties were taken over in 2001 by the foundation Kultuurileht.

of the Estonian art and visual culture quarterly magazine

Editor Heie Treier, designer Tõnu Kaalep

Despite the reference to the internet, registering a matching local .ee domain proved impossible, and the new trademark was approved only for printed products. The magazine gained a website at the address ajakirikunst.ee only in 2009, when the next three-person, part-time editorial team (Andreas Trossek, Heie Treier, Ave Randviir) began work. As a kind of conceptual comment on the austerity policies that followed the global financial crisis, it was intentionally designed as a “zero-design” site – the skeleton of a web environment originally built for a small private gallery, showing nothing but plain text and low-resolution images.

There was little choice: during the austerity years, there was no money for web development. The site has never felt the touch of a well-paid web designer and, as most service providers now confirm, would be nearly impossible to modernise technically. Yet the website, launched as a stopgap solution, has served the print magazine faithfully for many years, standing firm through endless software updates, server migrations and cyber attacks. It functions as an archive and a roadmap for navigating past issues and articles.

Compared with the almanac era, the new art quarterly certainly made more of an impression in print. The old alternation of black-and-white and occasional colour reproductions was left behind, and for most of the past quarter-century, the periodical has consistently been printed in full colour. Thick cover stock, stitched binding and a roughly 100-page volume mean that a single year’s issues sit on the bookshelf more like a solid art-history tome than a flimsy newspaper destined for the bin after reading.

The quarterly’s first designer, Tõnu Kaalep, initially wanted to emphasise a certain elitism and exclusivity even a bit more by adopting the square format of the legendary American art magazine Artforum. That idea, however, never progressed beyond the mock-up. What prevailed was Leonhard Lapin’s suggestion to copy the dimensions of almanac Ehituskunst (among others, his own edited periodical), whose production costs offered the most optimal balance of quality and price.

Today, of course, sustainability comes down to cost. Printing expenses are minor compared with labour costs. Nobody wants to work for free. A common line of thought – one that could be accused of a touch of naivety – assumes that if the state supports cultural journalism, then the result should immediately be freely available to everyone online. But the ministry also needs metrics to evaluate whether supporting a given publication makes sense, and those who look for them will always find them.

The magazine’s revenue base comes from annual subscriptions and single-issue sales. Online visibility may translate to fame and reach, but the magazine’s 2,800 Facebook followers do not equate to 2,800 paying customers. All back issues are, in any case, eventually digitally available for free in Estonia’s article portal DIGAR. Today, officials and advisers count subscription numbers; tomorrow… who knows, but presumably clicks. Yet for a niche periodical, shifting to the entertainment-driven “click economy” would be like going from the frying pan into the fire.

It is nonetheless remarkable how stable the quarterly’s subscriber base in Estonia has remained over the past decades. Times change, people come and go, economies rise and fall, wars begin and state enterprises are shut down – yet year after year, the number of subscribers has held steady at around 200, or just under. This is, incidentally, roughly the same number that makes sense in today’s modest Estonian book market when printing art catalogues or monographs. Fluctuations in subscription numbers are generally caused either by forces beyond anyone’s control – for example, in difficult economic times, an annual art-magazine subscription is hardly a necessity for most – or by discount campaigns.

The current record was set by the 2023 campaign, which pushed the total number of subscribers for the following year to just over 300. The lowest figures, unsurprisingly, date from the early years: 119 subscribers in 2002, 129 the year after, then 126. Predicting the future would be a thankless task, but one thing is certain: there is no trick that could bring about a categorical shift. In Estonia, an art magazine will never be ordered by stadiums full of people. It will always, by nature, remain a niche publication.

Is Kunst.ee the only one of its kind or irreplaceable? No. It never has been. You’ll find exciting art writing in newspapers, weeklies, magazines, online portals, on radio and television, in self-published exhibition leaflets and linen-bound museum catalogues. Not to mention the ever-expanding carnival of social networks, where everyone is an artist and everyone is a critic, and art is art is art.

And yet – noting that phoenix on the cover of Taie – does history not teach us that once a beautiful and ambitious idea has come into being, it is very hard to put it back in the bottle? In this case, the idea is that of an Estonian art magazine: a publication as comprehensive and as cross-generational as possible, one that makes art more interesting in the reader’s eyes and strengthens their cultural sense of self. Estonian art exists, really exists, has existed for a long time and is not going anywhere.

*

In a few years, it will be a full century since the first issue of the Estonian art journal Taie. What has changed in that time? Nothing has changed! Is the mission and vision not exactly the same? As proof, here is a selective quotation from its first editorial:

“Taie’s birth fulfils the long-held wish of many art lovers – to have a periodical devoted to art questions. Until now, art has received only occasional treatment in periodicals. Not many publications have given it the coverage it deserves alongside other fields. Taie wishes to continue [—] the work of popularising and researching Estonian art. Such an art periodical has become a necessity. [—] Let it be said briefly that Taie’s remit includes everything connected in one way or another to Estonian art and to art in general. Taie will present overviews and reviews of current art life, research and monographic writings on particular periods and artists, give space to theoretical questions, and record in its chronicle the most important events [—]. To carry out this broad and ambitious programme, Taie asks the public for goodwill and support and will do everything in its power itself.”

Andreas Trossek has been editor-in-chief of Kunst.ee since 2009.