Britta Benno, a board member of the Tallinn Print Triennial Foundation, and Marika Agu, curator of the 19th iteration of the Triennial, sit down to exchange thoughts and reflections after more than a year of preparations behind the scenes of this summer’s major printmaking event, taking place in the Tallinn Art Hall Lasnamäe Pavilion (21. VI–31. VIII 2025).

Marika Agu (MA): This year, the regional focus of the 19th Tallinn Print Triennial is the Baltic Sea. Participating artists are as diverse as Siim-Tanel Annus, Zuza BanasiŌ„ska, Mirtha Dermisache, John Grzinich, Maria Erikson, Doris Hallmägi, Semjon Hanin, Lauri Koppel, Maija Kurševa, Lauri Lest, Maria Mayland, Dzelde Mierkalne, Anna Niskanen, Algirdas Jakas, Tõnis Jürgens, Anne Rudanovski, Ülo Sooster, Anastasia Sosunova, Viktor Timofeev, Gintautas Trimakas and Taavi Villak. Before this whole process began, what kind of knowledge or experience did you have of the art scenes in the Baltic countries?

Britta Benno (BB): Honestly? My knowledge of what was happening in Latvia or Lithuania was pretty minimal. So in a way, diving into unfamiliar waters while preparing the Triennial was actually exciting – getting to know contemporary (print) artists from neighbouring countries. Of course, it’s a bit embarrassing that I hadn’t really taken much interest in Latvia or Lithuania before. The Nordic countries, Scandinavia and more distant corners of Western Europe just always seemed more exciting. Sure, I knew pretty well that Latvia and Lithuania, alongside Estonia, have always had a strong printmaking tradition and that they’ve always been represented at the Triennial. But I’ll be honest – I never really connected with their prints. Compared to the more airy and delicate style often seen in Estonian printmaking, theirs felt… dense. Brownish. A bit heavy. But I’ve completely let go of those old ideas now. I’m all in – ready to wade into the Baltic’s rich, brownish printmaking waters!

MA: When you’re working within the Estonian art field, what’s happening in neighbouring countries like Latvia, Lithuania or even Finland isn’t exactly served to you on a plate – you have to go out and find it for yourself. That said, international events like the Venice Biennale give you the chance to swing by the national pavilions and get a glimpse of what artists from those countries are up to. I remember when the 12th Baltic Triennial was held in 2018. It was spread across the capitals of all three Baltic countries, and for the first time, it really gave people a reason to travel to each within a short timeframe and get a sort of panoramic view. The first and second iterations of the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA) in 2018 and 2020 served the same purpose: to create a shared platform for contemporary art in the region. I remember seeing Anastasia Sosunova’s work at the second RIBOCA – that was the first time I came across her art, and now she’s been invited to take part in this year’s Print Triennial. And I’ve always had a soft spot for the “Survival Kit” art festival in Riga – it happens right around my birthday in early September, ever since it launched in 2009. I think it was back in 2014 that I visited the Contemporary Art Centre in Vilnius for the first time and saw an exhibition by Dainius Liškevičius. I’m still floored by the sheer physicality of that space – it showed me just how powerful a single exhibition hall can be.

But what made the board of the Tallinn Print Triennial decide to focus more on our own region this time around?

BB: Focusing on the Baltic countries felt meaningful on several levels. Over the years, the Tallinn Print Triennial has become incredibly international and grown into something huge – almost overwhelmingly so – with each iteration placing the spotlight on a different part of the globe.

The mission of the organisers, led by Eve Kask, has been incredibly valuable: bringing powerful works of art from all over the world to local audiences while also refreshing our networks and knowledge. The previous iteration in 2022, curated by Róna Kopeczky from Hungary, focused on Central and Eastern Europe, for instance.

But as the Triennial grew, it also drifted away – both from its local roots and from artists working in more traditional printmaking techniques. As a printmaker myself, I’ve found it hard to stay visible and recognised within that wider scope. My goal now is more print, more Tallinn – more local art and more of what the Triennial originally set out to be.

Putting the spotlight on Baltic art feels like a return to our roots. During the Soviet era, the Triennial was the main exhibition space for printmakers from the three Baltic countries. It served as a major international platform and a place where artists could exchange the latest ideas in both content and form. It’s a good time to renew those ties, build relationships with a new generation and strengthen our local base.

Continuity and sustainability aren’t just buzzwords – they’ve truly been core values throughout the Triennial’s 57-year history. The Triennial is more than just one exhibition. Its visual identities, photos, artworks, documents and catalogues together form a kind of evolving archive of our times.

There’s a political dimension to this focus as well. Especially after the full-scale war in Ukraine began, it’s become crucial to reinforce ties with our neighbours, to stand together and show unity. That matters now more than ever in our shared cultural space.

There’s also an ecological side to going local – scaling down a big exhibition and keeping it close to home. Whether it’s people, the environment or funding, resources are saved when we work slower, more locally and with less. And there’s a very practical upside too. Focusing on artists from nearby means you can visit artists’ studios more easily – something you and I, Marika, have done a lot of together. This is the best part of the process – having real conversations with artists in their workspaces in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

But as curator, how did you choose the artists, Marika?

MA: It was really great going to visit studios with you. Your printmaking insights were always so sharp, and I learned a lot. Every artist we met while preparing the Triennial was deeply committed to their work – real pearl divers in their field. I hope we can fit them all into one space, because the lineup ended up being quite a colourful mix.

With some artists, I wanted to continue dialogues we’d already begun in previous projects, and I’m happy they agreed to come along for the ride. For the historical works, though, I needed a bit of a push – someone to nudge me over the edge. I’m grateful to Elnara Taidre for picking up on my enthusiasm for Ülo Sooster and putting forward the idea of including his work in the Triennial. And now it’s really happening, even though both the Tallinn Art Hall team and the Triennial crew have had to work hard to make the temporary Lasnamäe pavilion suitable for exhibiting works from museum collections.

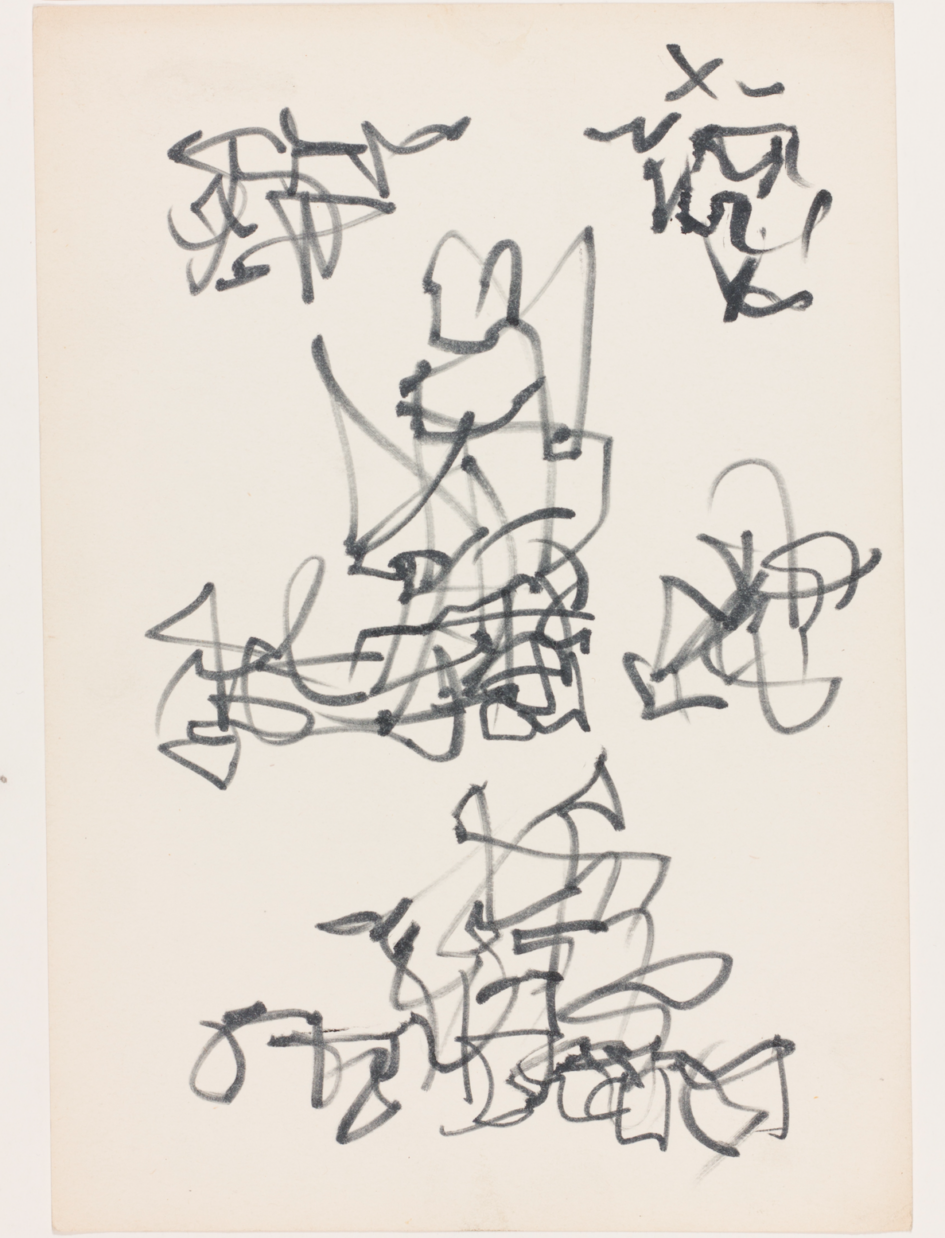

Ülo Sooster

Abstract motif

Undated (first half of the 1960s)

Felt-tip pen, paper, 28 x 20 cm

Tartu Art Museum

BB: Maybe even before getting to the artist selection, the real question is – where did the exhibition concept come from? As a curator, you already had some key ideas in place, like “asemic writing” and “a focus on paper,” well before picking the artists.

MA: I’d started to feel overstimulated by flashy spatial installations and flickering screens, and I wanted to offer something to counterbalance that – a show that would be unashamedly static, with artworks presented as framed “pictures”, so to speak. Behind this was a growing sense of information overload and the pressure to be available 24/7 for anything and everything. I began to notice that what gave me the most comfort at exhibitions were abstract works that didn’t aggressively demand my attention.

At the same time, I’ve long had a soft spot for tags and impulsive scribbles in city streets. There’s something irrational and raw in that gesture that I find compelling. When my kid was in nursery, he went through a phase where he’d draw letters – imitating writing without knowing how it actually worked. I suspect both phenomena express a fundamental human urge to leave a mark.

But our ability to receive and process those marks is limited, and I feel like we’ve now reached a critical threshold. These days, remembering anything seems to require a kind of prosthesis – a “smart guy in your pocket”. In this blur of split realities, analogue experiences that aren’t instantly shareable or accessible to all can have a grounding effect. Paper, in this context, feels almost like a prehistoric carrier of information – a subtle form of resistance to the relentless production of digital content. Paradoxically, though, it’s paper that got us here in the first place.

So what role does the Print Triennial play in developing printmaking techniques?

BB: Although the role of the Print Triennial appears to be the preservation of tradition, it has always been a revolutionary event as well, as Elnara Taidre describes in the preface to the book “In the Footsteps of the Tallinn Print Triennial”, published in 2018 to mark the event’s 50th anniversary. During the Soviet era, the Print Triennial offered audiences a glimpse of newer movements in print technologies and modes of expression. Since the 1990s, however, it has expanded to become a platform for all forms of reproducible art, thereby fundamentally broadening the meaning of printmaking. This shift was reflected in a freer approach to the medium, both in printmaking education and among artists, who gradually moved towards the interdisciplinary forms of a broader contemporary art practice.

Reproducibility has, for quite some time now, been the persistent drumbeat at the core of printmaking. There are constant references to Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, 1935). Today, when all media are reproducible down to the molecular level and everything spreads and multiplies uncontrollably in virtual reality, reproducibility is no longer, in my view, the sole or primary characteristic of printmaking. Many artists working with printmaking techniques no longer produce editions at all. That is, they do not print a controlled series of identical impressions but create their printed works as unique pieces. For example, the works of renowned Estonian printmaker Kadri Toom are more akin to paintings, existing as unique pieces rather than editions. Technically, it is not even possible to create multiple identical works using many printmaking techniques – yet in my view, this does not make these works any less of a form of printmaking.

Printmaking techniques encompass a remarkable wealth of layers – of meaning, memory, material and surface – through which broader themes are explored. For example, in her podcast, American art historian Jennifer L. Roberts divides printmaking into six core manoeuvres: pressure, reversal, separation, strain, interference and alienation. This approach is intriguing and offers a new way of engaging with the work of printmakers on a deeper, more conceptual level.

Knowledge of printmaking shapes an artist’s way of thinking and their artistic handwriting, even if they no longer work directly with printmaking techniques after their studies. For example, this distinctive way of thinking and sensitivity to materials is evident in the work of Lithuanian artist Anastasia Sosunova, who is among the participants of the 19th Tallinn Print Triennial. Her etched copper plates, integrated into a larger installation, have a powerful presence: the metal seems to have been liberated from its role as a mere tool and has become a self-sufficient element within a broader, multilingual narrative. The metal plate also plays a significant role in the drawings of Lithuanian artist Algirdas Jakas, where an ominously gleaming offset plate, the soft line of coloured pencil on paper, and hand-cast plastic screws piercing the surfaces are woven into a contrasting, layered composition. Latvian artist Dzelde Mierkalne moves beyond etching to create sculptures from marble-like cement using the scagliola technique, into which she engraves. Her dreamlike, Mickey Mouse–like figures playfully reflect existential fears and anxieties.

MA: It is very good that you have already highlighted some important names contributing to the development of the printmaking field. You have mentioned in our conversations that printmaking has long been overshadowed by other artistic media. What’s the reason for this?

BB: During my studies in the late 1990s and early 2000s, printmaking was not in fashion. We were told by our teachers that printmaking was “dead” and that we should focus on something else. Defiance is a powerful motivator, and it only strengthened my desire to continue making prints even after my studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts. It is an incredibly versatile medium – flexible in every direction, evolving over time, yet intriguingly woven into tradition. It allows for both conventional and radically deconstructive approaches. For a long time, printmaking was not considered trendy. It was relegated to the realm of craft and seen as overly decorative and old-fashioned.

Today, however, these perceptions have completely shifted. Craft as a form of resistance to haste and the agency of materials – where the “genius artist” no longer works or decides alone – has brought fresh air not only to printmaking but also to other material-based art forms. Virtuality did not kill printmaking; one did not replace the other. Instead, multiple phenomena now coexist and operate simultaneously within an expanded space.

Yet between the old truths and the new movements, one generation somehow got caught between the gears – unrecognised by the old and already bypassed by the young, who are operating within a new realm of perception. So I am pleased to see that the position of printmaking in the art world is being rehabilitated. At the Venice Art Biennales, I can already count more drawings and print works than I have fingers on one hand. I am also glad that the Print Triennial here is contributing to the renaissance of material-based arts.

But what draws you to printmaking? Why is it important to you? And how did thinking about printmaking lead you to the broader development of media and artistic techniques?

MA: The Print Triennial has been a great outlet for my obsession with line-based forms – including, for instance, different typefaces. I’m really grateful that the Triennial allowed me to give the exhibition an illegible title. In my view, it takes the idea of typographic potential to its logical extreme, allowing people to read and mentally store it however they like – in defence of chicken scratch!

Partly inspired by the architecture of the main exhibition venue – which can practically be read as an endless loop where the start connects seamlessly to the end – I began to imagine the life cycle of a graphic form: how it’s born, where it dies, and everything that happens in between. The show explores personal sign systems, note-taking and the struggle to retain what we’ve experienced, all in the context of information overload caused by our electronic devices – and the temptation to constantly produce even more.

I built the exhibition as a kind of associative, step-by-step journey. And then, in the final phase of the project, I discovered that media theorist Alessandro Ludovico has been thinking about similar things – especially concerning the evolution of analogue and digital media and how to navigate information excess. That’s why we’ve decided to include a couple of his essays in the Triennial publication and to invite him to speak in Tallinn on 21. VIII 2025.

BB: One new thing you’ve introduced is a closing event for the Triennial – on 29. VIII 2025, beside the Lasnamäe Pavilion at the Lindakivi Culture Centre. You’ve curated a special lineup of sound, performance and video art for the occasion. What made you want to separate these time-based works from the rest of the exhibition and bring them all together in one unique evening?

MA: The first reason was practical – launching a summer exhibition just before Midsummer’s Day means it can be tricky to attract an audience, so the idea was to catch people at the end of summer instead. Second, there’s the fact that we have access to great tech right next door to the pavilion. And third, thinking again about our overstimulated, attention-fragmented age, I felt that time-based works deserved a dedicated moment and space, rather than having someone randomly stumble across a ten-minute video or performance in a gallery, half-distracted.

Even though it might seem self-evident that the Tallinn Print Triennial should showcase printmaking, that hasn’t always been the case. Thus, introducing a kind of media-based retrospective distinction feels not only relevant but necessary. By bringing experimental poetry, sound and moving images into the Lindakivi Centre for one evening, I think both the artists and the audience stand to gain something special.

BB: Amazing! Hopefully the summer holiday season will bring plenty of tourists from nearby to the exhibition. You and I are doing our part by bringing Baltic artists to Lasnamäe. It’s shaping up to be a real graphic summer – here’s to a great celebration!