SUMMARY

It is no surprise that the play of light and colour in churches is often compared to the shimmering precious stones of the walls of the heavenly Jerusalem, as described in the Book of Revelation (21:18–21). Human imagination struggles to grasp the splendour of this city. Yet, through its unique ability to transmit light, stained glass brings us closer to understanding the divine light that permeates the world.

For Estonian-German stained glass artist Dolores Hoffmann (b. 1937), light is the essence of stained glass. Because of this, stained glass is never static – it changes constantly with shifting light, the movement of the sun and clouds, and the passage of days and seasons. As Hoffmann puts it, stained glass is in “constant vibration”, reflecting “every movement and the shimmer of the sun and the entire space around it”.

For example, the rays of the rising and setting sun enhance and transform the vibrant tones of stained glass, their intensity inextricably tied to the choice of glass. Sunlight, interacting with a vast range of colours and shades, creates what Hoffmann calls the “astral sound of colours”, lending stained glass an almost musical quality. “Rhythmically arranged coloured light affects not only the conscious mind but also the subconscious. It is a pulsating energy, akin to the melody and energy of sound. Of all the visual arts, stained glass is closest to music,” she says.

While stained glass has a centuries-old history, its golden age coincided with the rise of soaring Gothic cathedrals. Among these, the stained glass of Chartres Cathedral holds a particularly important place, especially the monumental three-window cycle on the western facade, which dates back to around 1145. Rich red and deep blue dominate the colour scheme, with the latter now famously known as “Chartres blue”. The cathedral’s interior contains over 170 compositions spanning more than 2,000 square metres, a testament to the scale of craftsmanship involved.

It is worth noting that master glaziers did not always themselves carry out every stage of the process, from drafting to glazing – much depended on patrons and donors. Often, artists created the designs, as was the case with the stained glass of St Sebaldus Church in Nuremberg, crafted by master Veit Hirschvogel (1461–1526) based on sketches by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). However, transferring these sketches onto full-scale cartoons for cutting the glass was typically done in the workshop.

From the first drawing to the finished window, stained glass passes through multiple stages and many hands. In this sense, it is always a “collective endeavour” and requires “a division of tasks within a team”. The role of the master glazier is crucial – without them, the stained glass artist cannot bring their vision to life. “No master – no stained glass,” Hoffmann says. She herself does not physically create stained glass but only designs it. Her sketches are shaped by imagination, knowledge and experience. She insists on drawing full-scale cartoons by hand, without relying on computers or assistants, as only this ensures “the tension of the lines” in the final work.

Translating an artist’s vision from paper to glass, breathing life into it, is the master glazier’s task – finding the right one is like winning the lottery, a matter of luck or even divine providence. “The relationship with the master is the most important and the most complex aspect,” Hoffmann explains. “It is a peculiar compatibility on many levels, not always analysable (nor does it need to be – it lies beyond our understanding). It simply emerges.” She met her first master glazier – who later became her life partner and followed her from Leningrad to Tallinn – in 1974. Their creative partnership lasted for decades.

Over time, several master glaziers trained in Hoffmann’s Tallinn workshop. To date, she has created stained glass for 34 churches in Estonia and for many religious and public buildings outside Estonia, including in Batumi, Georgia. With Hoffmann, Estonia’s stained glass tradition truly began.

Hoffmann’s love for stained glass, which she came to after working with fresco, sgraffito and mosaic, began with Chartres Cathedral – or rather, with a book about it. The Chartres album, acquired with great difficulty from a Finnish acquaintance, became her gateway to the art form. In the Soviet Union, religious imagery was banned as “propaganda”, and examples of stained glass in Estonia were virtually nonexistent. Alongside a 1939 brochure on medieval stained glass, this book became her primary source of learning. When she finally visited France in 1993, the director of the International Stained Glass Centre in Chartres, after reviewing photographs of her work, asked where she had trained. To him, her work seemed to represent the “Chartres school”. In this sense, it is fair to say that Hoffmann’s style and artistic language were shaped by the traditions of medieval Europe.

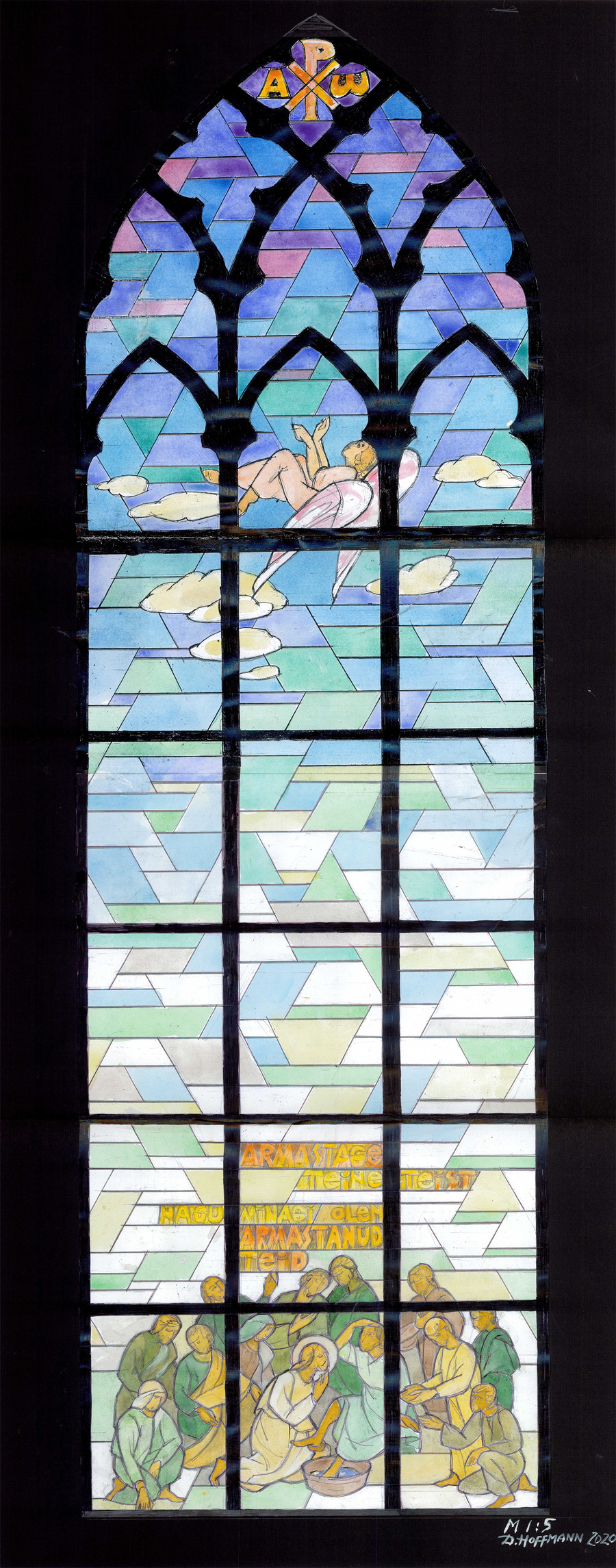

Dolores Hoffmann

Stained glass window at St John’s Church in Tallinn

2019–2022

Photo: Toomas Tuul