28. IX 2023–3. III 2024

Fotografiska Tallinn

In front of the pictures

Toomas Volkmann’s photo exhibition “pastful blast” is very “full” indeed – the pictures in various formats that fill several halls are too many to be counted, nor would there be any point in doing so. The artist has composed them as entire constellations on different walls and in different rooms, so that the general impression is that of the “past” becoming a recreated “present”. Hence the title: “pastful blast”.

Behind the pictures

Toomas Volkmann’s domain is art photography. To be sure, he has also photographed more frivolous subjects, but the core of his work should not be viewed as current affairs photography. We should focus our attention on nothing behind the scenes – not the technical equipment used nor the price of the picture frame, nor wonder whose property this leafless tree or that shabby hut stands on. The model’s name and age are immaterial to the work. In fact, even knowing the year the shutter release was pressed is superfluous (you shouldn’t read the labels) because art is timeless; it is a present born at the moment of viewing, a glimpse of the artist’s mortality or immortality.

Of the three questions – what? where? and when? – only the first is of artistic interest. What is in the picture? Not the reality behind the picture! Not “album photos”, but “gallery photographs”.

Only what is stored on the surface of the picture.

In the pictures

Toomas Volkmann’s “pastful blast” is a sensitively articulated world laid out in two dimensions. Meaningful portraits (a little dictator brat and Arvo Pärt, both with a finger raised) become independently evocative thanks to alternating with non-descript decorative panes (a pile of grass between them). At times, the designer seeks to imbue the flanking portraits with some of the meaning of the interposed image (a bonfire between the faded topless model and the old lady with a burning gaze), but this effect either remains weak (Elsa with a veil – Mapplethorpe-like corncobs – a dwarf with a broken angel) or feels forced (Jänes with closed eyes wearing makeup – a rusty cauldron – Aldo with prosthetic hands). A captivating combination forms out of a series of four pictures where the image of a church cuts off a woman wearing a veil on one side, leaving a delicious pair out of a Hitlerjugend era trio and a Mussolini–Fellini era diva on the other.

Photographs that the artist has not had the heart to leave out form patterns where the placement of specific images amidst others tends to overshadow the message of each one (the smokers’ wall as a whole). In most cases, the message of these images feels slight (a young man sitting, with creased trousers hanging low; a voluptuous girl in an armchair) or muted (a rapper looking deranged, a female pop singer with black gloves).

A handful of photographs form more coherent visual syntagmas. From these, equally strong images can be picked out (a panel connected with outstretched arms). Some individual images stand out on their own. From the composition of eight portrait faces on the left, three boys are looking back at us: the one with short hair has a dead gaze (a “noun image”, which only answers the question: who?); the shaggy-haired one looks theatrical, like a model (an “adjective image”, which answers the question: like what?); the third one, though, has that je ne sais quoi gleam in his eyes, the inexplicable something that makes an “adverb image” – the most valuable one in the entire palette of portrait genre (the same goes for the image of Sirje Runge and the twins).

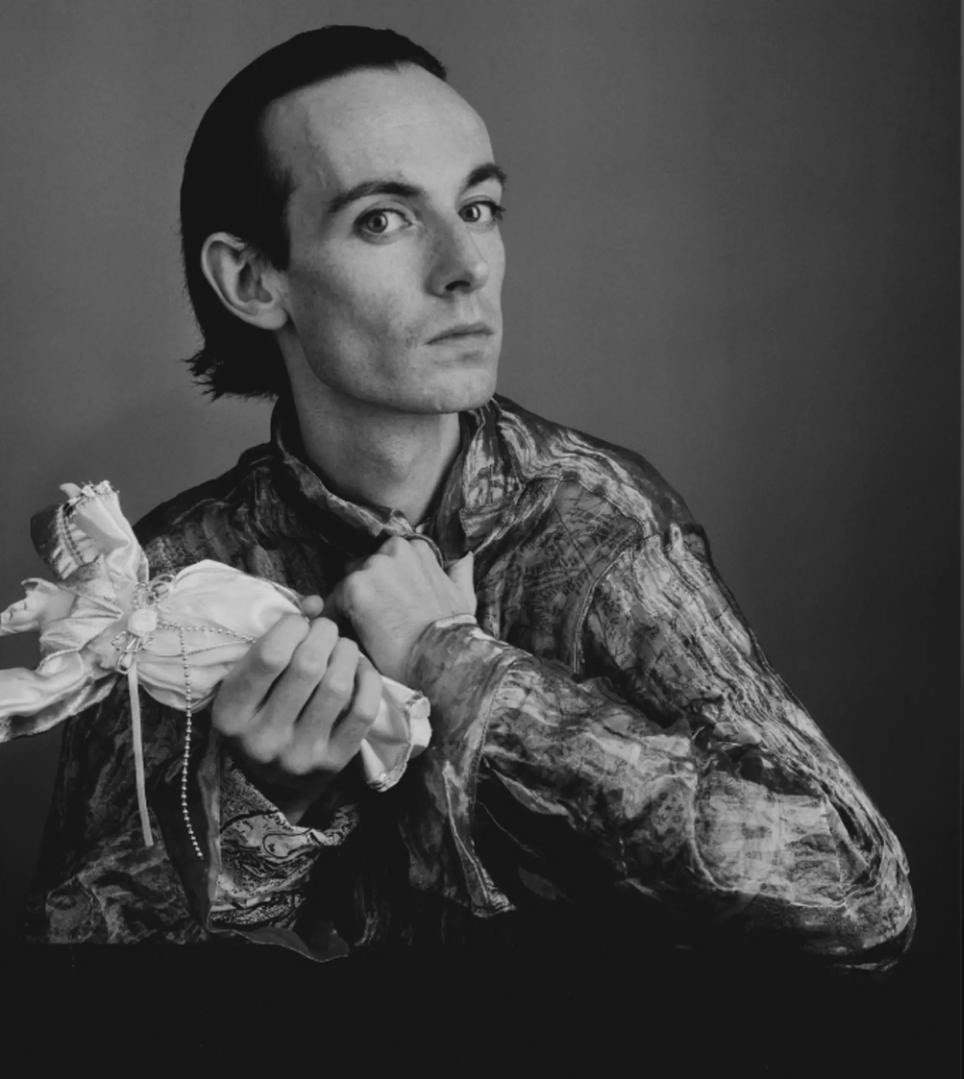

As a portraitist, Toomas Volkmann stages his works as a combination of model and attribute, following the tradition of Renaissance art (in 1995, I published a detailed analysis of his picture of Johnny, in the context of Albrecht Dürer’s self-portraits, in Magneet magazine). These images are structured as a fugue: the person as dux and the object as comes, within a developing contrapuntal relation of meaning.

There is a subtle but significant difference between the earlier portraits, which the artist himself wanted (!) to take, and the later ones, which he was able to (!) make, either for a fashion magazine (a girl with a pig’s head) or to order (the actress Ita Ever, an old gentleman adjusting his tie). The former feel fresher, more intriguing: a (semi)naked young man with a vicious look in his eye, posing with a bunch of grapes and a knife; a defenceless-looking young man holding a glass flask; a girl stretching a wig; another girl squashing strawberries. There is an abundance of enchantingly flawless creative stagings.

Toomas Volkmann

Johnny with Broken Angel

1994

Black and white photography

Art Museum of Estonia

Toomas Volkmann’s best photographs are characterised by an inner artistic seriousness, if by this we mean the opposite of triviality, a certain sense of responsibility and personal commitment, which is alien not only to the spirit of our time but also to temporality as such.

His element is black and white. He uses colour photography only to capture objects (a broken icon amidst peonies with falling petals, a pomegranate that has been split open, roses) and even in colour photographs of costumes, carnivals, social events (a “young Shirley Temple” and a young man doing wall splits appearing as mere bright-coloured accents; a transvestite with a pink tutu; a wallpaper for the Vibe party series) the colourful models themselves become objects that arouse only external interest. By contrast, objects in black and white (corncobs, asparagus with safety pins, again Mapplethorpe-esque dripping tulips) come to life in front of his camera.

The general impression of this survey exhibition crystallises our understanding of the artist’s essence. Toomas Volkmann represents an aristocratic visual aesthetic, but rather than a “hereditary nobleman”, he holds honorific status as a self-made aristocrat.

The past does not last; it continues. To conclude his private tour of the exhibition on the day before All Souls’ Day, the photographer said: “Tomorrow, I’m going to shoot…” – Who? He said who, but it doesn’t matter. I once asked Toomas if I should go and get a haircut before his photo shoot, and he responded: “Never mind that! You should rather ask me what I’m going to wear when taking your pictures!”

Linnar Priimägi is a phenomenon.