18. XI 2022–9. IV 2023

Kumu Art Museum, 5th floor, gallery of contemporary art

Artists: Victor Alimpiev, Vladimir Arkhipov, Jčnis Avotiņš, Matei Bejenaru, Blue Noses Group, Vajiko Chachkhiani, Olga Chernysheva, Kristaps č¢elzis, Dmitry Gutov, Severija Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė, Rasa Jansone, Jčnis Kalmīte, Alice Kask, Vendula Knopová, Eva Kot’átková, Leonards Laganovskis, Goshka Macuga, Inga Meldere, Rustam Mirzoev, Deimantas Narkevičius, Mircea Nicolae, Lucia Nimcová, Adrian Paci, Ievgen Petrov, Joanna Piotrowska, Tõnis Saadoja, Krišs Salmanis, Monika Sosnowska, Antanas Sutkus, Artur Ō»mijewski

Curator: Eda Tuulberg

The selection of what to remember and what to forget is part of the construction of the present, an act that contributes to the classification and systematic ordering of things. The same is true of collecting, which is one way – like any other – of putting things in order.

Twenty-two years ago, Irina Vītola and Mčris Vītols decided to form an art collection of their own, a collection that would reflect on the political changes in Central and Eastern Europe and include a large number of video art pieces. To my understanding, there is no similar collection in the region. And that is probably the reason why Kumu Art Museum decided to organise this kind of exhibition.

One colleague, however, comments that he does not understand why Kumu is helping to glorify a private collection, noting that there are other spaces in Tallinn to do so (where “this kind of show would not seem out of context”). Another colleague, Rebeka Põldsam, notes the incongruency of how Kumu went from being extremely cautious about showing Soviet symbols, as was the case in the exhibition “Thinking Pictures” (18. III–14. VIII 2022, curated by Liisa Kaljula and Anu Allas), to displaying them in a humorous way as in “Archaeologists of Memory: Vītols Contemporary Art Collection”.1

Regardless of whether we agree or not, both criticisms are legitimate. Exhibitions revalue collections and play a key role in art appearing as art, while writing some works into the pages of art history.2 Hence, we can bring up further questions about the role of public museums, such as Kumu, in contemporary societies.

Represent the past until it breaks

We can assume that Mčris Vītols agrees with what is written on his Wikipedia page and has chosen to present himself on the basis of his hobby and his former profession: “a Latvian art collector and a former politician”3. Collecting and dealing with memory share a similar impulse: a form of sorting social relations and an attempt to attribute a stable and ordered significance to something that did not have it before. The most difficult part, I reckon, is selecting what not to remember, what to ignore.

One difference, perhaps, is that the formation of memories is way more unpredictable than collecting. Memory deposits are much more than static remnants, forming a complex assemblage through obsessions, revisions, re-presentations and oscillations between the outside and inside. The re-presentation of this dialectic was included, for example, in the exhibition “Archeological Festival_ a 2nd hand history and improbable obsessions” at Tartu Art Museum (19. VI–24. VIII 2014, curated by Maria Arusoo).

Memory is more than a subordinate to human actions. It is a declaration of necessity, manifested as an urgency to deal with what has already passed – and which is subsequently qualified as a burden or as a treasure. In some other cases, memory can simply be stored in the body, an archiving gesture that can happen in multiple ways, as we see in the works of Victor Alimpiev, Joanna Piotrowska and Lucia Nimcová.

The past does not love us anymore

Through various works included in “Archaeologists of Memory”, we are part of diverse temporal experiences, of accelerations and stoppages, of boredom, hangover and thrilling moments – as was the transition period in Central and Eastern Europe. An alternative approach could have been to invite young artists to dialogue with or complement some works in the collection – also to revise the connections between art and archaeology.

“Archaeologists of Memory” is based on three key ideas: personal attitudes to memory, socio-political changes in Eastern Europe, and art collecting as a practice. Nevertheless, the interconnection between these topics is not sufficiently explicit. The audio guide helps us to understand the general approach, but visitors rarely use these devices.

I guess it was a challenging task to select from a personal collection that gathers nearly 1,000 works. Alas, there were works, such as the “Rija ” series (1970–1985) by Jčnis Kalmīte or the installations by Monika Sosnowska and Severija Inčirauskaitė-Kriaunevičienė, that I would not have included. Nor would I have placed the video “Romanian Kiosk Company” (2010) by Mircea Nicolae at the very beginning. It is indeed a touching work, but slow and narrated with not the most pleasant voice. As a result, visitors hardly dedicate more than a minute to it.

Most of the artworks included in the show share an obsessive and bizarre tone, like “Tutorial” (2015) by Vendula Knopová, a best-of compilation from her mom’s hard drive, or “Lost Treasures” (2008) by Rasa Jansone, who placed ghostly objects in amber to nullify their ghostly effect. They both show how each generation tells the past again and again – a past that was never there as such.

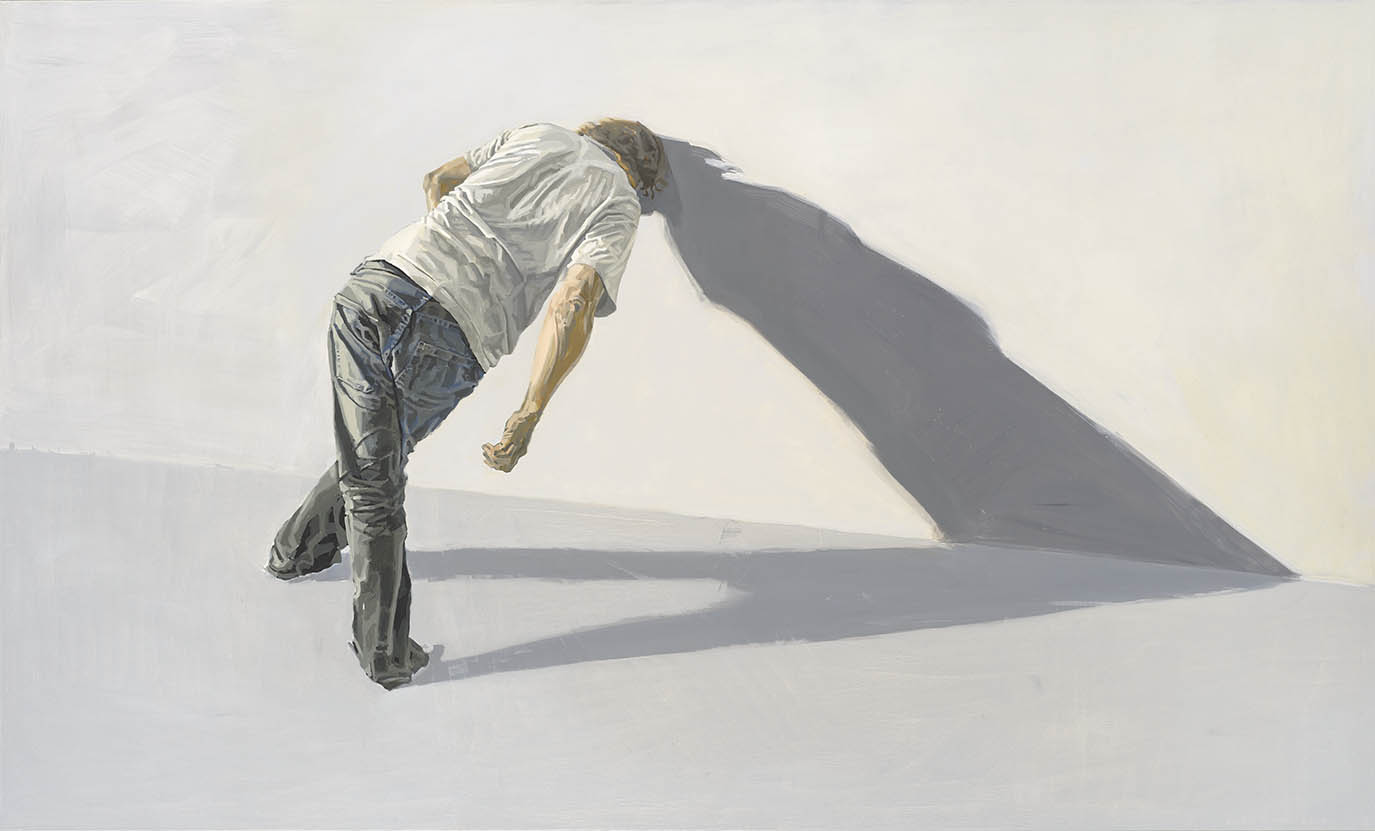

Alice Kask

Untitled

2009

Oil, acryl on canvas, 150 x 250 cm

Photo by Stanislav Stepashko

Vitols Contemporary collection

The ages of memory

In the exhibition catalogue, Tanel Rander discusses what Eastern Europe means these days. We could question the explanatory value of this geopolitical category in the present, or even talk of a “zombie category” that refers to a “non-region”. It would have been more interesting to pay attention to how young people are recalibrating narratives of the socialist past in the present. They certainly inherited the historical representations and cultural forms of their parents, but the younger generation has the agency to change these.

Alas, Mčris Vītols describes it as “naïve” to believe that the cultural forms created around the Cold War era have been overcome and insists on the separation of Western and Eastern Europe. This private collection reflects such a position well, and he has clearly been buying art that reinforces his worldview. In his words, the art of the “non-region” is a “poetic conceptualism”, characterised by a particular sense of humour and a gesture desacralising socialist symbols (i.e. Blue Noses Group).

The particular structure of feeling and political kinship that seems to interest the collectors is also exemplified in the para-modern sculptures of Vladimir Arkhipov. The Vītols’ collection also includes artworks that deal with the side-effects of a past future gone. Like Artur Ō»mijewski’s “Singing Lesson” (2002), a haunting video that demonstrates a choir in which the participants cannot hear what they are singing, or Vajiko Chachkhiani’s hypnotic video “Winter Which Was Not There” (2017), which explores how people’s feelings and imagery vanish at a different speed than built materials.

The exhibition design by Anna Škodenko and the graphic design by Viktor Gurov are both subtle. In the exhibition, we step into the darkness and end up with light; each room whitens its coat of paint as if in step with the memory work. The motto of such a design is also mentioned in the catalogue by Eda Tuulberg, the curator of the exhibition. Basically, the belief is that remembering and healing go together, and both the exhibition designer and the curator present this act as a therapeutic way of addressing traumas.

Alas, stories from and about the past are not always a lesson for the present. They do not help us to project ourselves into the future, though they might give us some tools and solace for coping with the hardships of the present.

1 Rebeka Põldsam, Ümberhindamise aasta. – Sirp 16. XII 2022.

2 For more detail, see: Fernando Domínguez Rubio, Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art Museum. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

3 See: https://lv.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C4%81ris_V%C4%ABtols.

Francisco Martínez is an anthropologist. He is a visiting professor at the Estonian Academy of Arts and head of the Social Design MA programme.