The core of the programme for “LadyFest Tallinn” (8–12 March) was the exhibition “Welcome me Estonia. Добро пожаловађь мне в ÐÑђонии. Tere tulemast mulle Eestis” at the Rundum artist-run space (Pärnu mnt 154, Tallinn). The exhibition was created with refugees living at the Accommodation Centre for Asylum Seekers in Vao, who for a few months participated in a weekly art class organized by the committee for “LadyFest”. The art classes were guided by Minna Hint, Mari-Leen Kiipli, Pire Sova and Killu Sukmit.

The exhibition defined the conceptual backbone of the festival and was complemented by movie nights and workshops. The programme of the festival was marked by events that articulated feminist perspectives on the subjects of migration and racism. My analysis focuses primarily on the exhibition project I am interested in the exhibition’s relationship to the social context from which the festival derived its programme this year.

What is the social context of the “LadyFest” exhibition?

The debate on migration arrived in Estonia in the spring of 2015, when the European Commission proposed that asylum seekers looking for international protection in the European Union should be distributed between the EU Member States according to quotas. The background to this proposal included processes that had been cumulating for many years – military conflicts and humanitarian catastrophes in the Middle East and Global South, the growing amount of asylum seekers in the European Union and tragic deaths on refugee boats in the Mediterranean. An attentive political observer would have certainly recognized already a few years ago that these events have a far-reaching impact that will sooner or later affect Estonia as well. Yet this awareness did not come to the public consciousness until last year, when the local media began to talk about “a refugee crisis”.

In Estonia, the crisis has very little to do with the large-scale migration processes that in many other countries around the world have pushed the limits of the administrative capacity to ensure refugees a safe passage or elementary living conditions. For the past year, the number of asylum seekers in Estonia has remained stable at around 100, but the influence of international news has created a public atmosphere of crisis, characterized by a massive polarization of the public space. On one side, the small proto-fascist parties and anti-immigration movements call for the defence of the supremacy of the white race with barbed wire and violence, at the same time, on the other side, liberal civil society defends its class position, marking the limits of its tolerance with declarations of solidarity with the refugees of war and the condemnation of economic refugees. There is a lot of discussion about refugees, even though the problem is racism. The only group whose voice is almost never heard in this debate is the refugees themselves.

While sharp arguments over refugee issues are being exchanged in the public space, there are only a few initiatives that relate to the asylum seekers who have arrived in Estonia. Supporting refugees is largely left in the hands of the state administration. The state services are complemented by some non-government organizations, whose activities primarily focus on material and legal assistance. In addition, there are a few grassroots initiatives operating according to the same logic, for example by collecting material help for the asylum seekers at the Vao accommodation centre or supporting them in communication with state institutions or search for a place to live and a job.

The practice of organizing art classes, initiated by “LadyFest”, can be conceptualised as an example of practical solidarity work, which is a strategy that is rather uncommon in Estonia. The art classes were motivated by curiosity and a desire to support refugees, whereas the tools used in this process are precisely those that artists are most familiar with. This kind of solidarity work is quite different from the dominant strategies of civil society, which so far have addressed “citizens” in the national-sovereign sense of the word. The solidarity projects initiated by civil society, such as “Friendly Estonia” last year, have tried to influence public opinion by inviting the majority that already enjoy civil rights to express greater tolerance towards the less privileged minorities.

In contrast to this, the approach taken by the “LadyFest” committee is aimed at the micro level. Instead of the human rights discourse, human contact is at the core. Consequently, it turns out that by using their own tools, artists really do have the capacity to address blind spots that fall outside the sphere of the attention of civil society. These spots are mostly related to the affective aspects of the asylum seekers’ daily lives, such as the constant waiting for a positive response to their asylum applications, the forced inactivity in an isolated accommodation centre, post-traumatic stress and uncertainty about the future.

Organizing art classes as an activist strategy might seem unpretentious at first glance because it seems to abandon any ambition for a systemic political change. However, this method is significant precisely because of its simplicity. First, because it is derived from the specific needs of the asylum seekers, which in the conditions of the Vao centre primarily means their yearning for something to do, and second, also because the strategy is based on pleasure – a banished concept that is unanimously avoided in debates surrounding the “migration crisis”.

How is the “LadyFest” exhibition positioned in the feminist context?

To begin with, it is worth mentioning that during the period it has operated in Estonia, “LadyFest” has carried a special role in mobilizing the feminist publics. Before the emergence of “LadyFest”, feminism in Estonia was for a long time scattered into small islets, whose strongholds were located mainly in the arts, in academic circles or in the state-administered gender equality policy contexts. Six years ago “LadyFest” was one of the first platforms that started to actively encourage and facilitate feminist dialogue through its cross-cutting programme.

Another important forum that has occupied a central position in shaping the feminist public is the group “Virginia Woolf sind ei karda!” (Virginia Woolf is not afraid of you!), created on the social media platform Facebook. The genealogy of both forums reaches back roughly to the same initiative group and the same period of time, but their development has been very different. While the Woolf group functions mainly as a place for negotiating feminist minimum consensus, then “LadyFest” has consistently tried to formulate topics and stimuli to challenge the mainstream. The web magazine Feministeerium.ee, created in 2015, has emerged as a third important stronghold for mobilizing the feminist publics.

Through these initiatives and with the confluence of current social debates, feminism has grown a large social base in recent years. This is an extraordinary moment because feminism has probably never had such a strong position in Estonian society. But who are the feminist subjects in Estonia? This is a critical question, which on the current wave of feminist mobilization, has started to function as a frame for collective self-reflection. For example, the recently published article by Redi Koobak “Millest me räägime, kui me räägime feminismist Eestis?” (What are we talking about, when we are talking about feminism in Estonia?) reveals that Estonian feminists are increasingly reflecting on their social class context, in which the most visible subject position is a highly educated middle class woman who is an Estonian native speaker.1 Yet it is striking that, even though the privileged position is acknowledged and problematized, the discussion often stops there.

The exhibition “Welcome me Estonia” is significant in light of these dynamics because it is looking for strategies to break the elitism of feminist practice. In the context of art, “LadyFest” is not the first project to present itself such a challenge. Another notable example is Nancy Nakamura’s Shelf of Ideas, which operated in Kopli between 2013–2015, lead by Kadi Estland and with the participation of many artists belonging to this year’s “LadyFest” committee. Her self-initiated project space was looking for strategies to bring cultural and feminist impulses into a context in which the social composition is dominated by the Russian-speaking working class.

I was only able to remotely observe the activities of the Shelf of Ideas, and on the basis of this I have formed an impression that in most cases their attempts to relate to the local context were rather weak. The programme of the Shelf of Ideas was mainly formed on the basis of the interests of the dominant feminist subject, except for the art camps for children organized under the name Kopli Kullo. Therefore, it seems that art lessons have become the preferred method for feminist artists seeking to build social bridges.

Where is the feminist dimension of organizing art lessons? The most interesting responses to this question come from practical experience. For example, the committee for “LadyFest” noticed that for many women who participated in the art classes in Vao, it was the only opportunity to leave their children under someone else’s care, and focus on themselves for a moment. Therefore, organizing art lessons does in fact relate back to the feminist core narratives which are based on a pedagogy that is anything else but a doctrinating one. It is a pedagogy of listening, in which “a room of one’s own” is central – a room to be with oneself and to articulate in your own voice.

How is the “LadyFest” exhibition positioned in the context of contemporary art?

When analysing the exhibition “Welcome me Estonia” from the perspective of art criticism, then it most comfortably fits into the category of participatory art. In Estonia, community art is still located in the periphery of the art world, and in this sense the exhibition project for “LadyFest” is quite unique. In the context of Estonia, it happens fairly rarely n that artists act collectively or build their practice on collaborative processes.

It is quite typical for participatory art projects that only the end result or the documentation of the collective processes is presented in the exhibition space. The exhibition visitors can only experience participatory art under certain limitations because the exhibition is usually not able to transport the inner dynamics of processual art projects, the negotiations, contradictions and shifting subject positions that occur during the process. Participatory art theorist Claire Bishop has critically pointed out that art criticism’s criteria for analysing community practices are primarily based on ethical principles, paying less attention to the aesthetics.2 Although I agree with Bishop’s statements in several respects, I do not think that discussing ethical issues has a reductive affect on the aesthetic qualities of art. These two dimensions are mostly inextricably linked.

The basis of many participatory art projects is the artistic position of the artist, which offers a very narrowly defined role for the “participants”. Such artists include some of Claire Bishop’s favourites, like Artur Ō»mijewski or Santiago Sierra, who are trying to challenge the ethical boundaries of the art audience. Often, the core of their work is a very powerful aesthetic image, through which the viewer is turned into a participant in borderline ethical situations. The participation of communities or individuals in these projects is generally subject to the artist’s vision. On the other side of participatory art, there are egalitarian and open processes that create spaces, where new relationships and experiences can develop. These projects are often dialogical and processual and don’t necessarily aim to create visual images. Most participatory art projects operate between these two strategies, and therefore, it is appropriate, in the context of participatory art, to ask about the artist’s intentions.

When discussing the “LadyFest” exhibition, it is worth mentioning that this year’s organizing committee is composed entirely of artists. Looking at the history of the exhibition, it gives the impression that this is the subject position that has in many ways defined the motivation of the committee. For example, the idea to offer art classes in Vao was, from the beginning, associated with a plan that would result in an exhibition. Exhibitions have a special place in the economy of the art world because they motivate artists to operate in conditions they would not always agree to in other contexts. When the committee for “LadyFest” started to make weekly trips to Vao in November 2015, they did so initially at their own expense and only later, during the process, started to look for public funding that would cover the costs of the project. By contrast, at the opening of the exhibition, the organizers were unsure whether they would be willing to continue to cover the costs of organizing the art classes, although the residents of the Vao centre had unequivocally expressed their interest in continuing the workshops.

This is a significant fact that shows that the committee for “LadyFest” did not go to Vao solely as feminist activists, but also as artists motivated by, among other things, the desire to report their activities back to the art scene through an exhibition. I do not think that the artists’ desire for recognition and visibility should be subjected to moral evaluation. I just want to draw attention to the fact that this desire is a constitutive element of the “LadyFest” exhibition project, which distinguishes it from activist solidarity work.

Another aspect that I would like to draw attention to refers to the power relations inherent in this project, which were amplified at the exhibition. Looking at the media coverage of the “LadyFest” exhibition, we can see the reproduction of some patterns, the breaking of which actually formed the initial stimulus for the project. Only the representatives of the committee, to whom the artist’s position and political agency is attributed, spoke about the “LadyFest” exhibition. The newspaper headlines praised how “LadyFest” gives a voice to asylum seekers”,3 even though the word was given, once again, only to the privileged feminist subject. But where then are the voices of the asylum seekers and how do they sound?

LadyFest Tallinn 2016

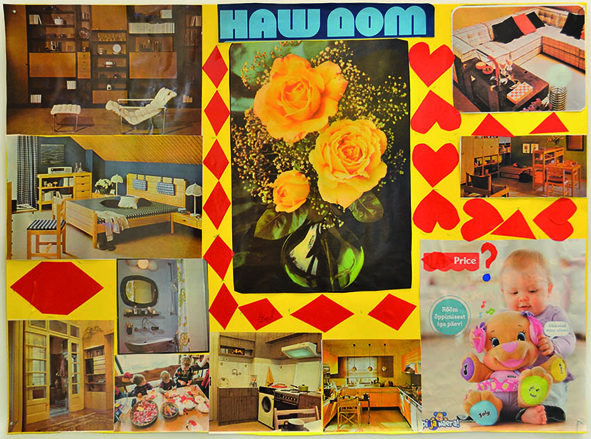

Exhibition views at Rundum Art Space

Photos by Eve Kask and Mari-Leen Kiipli

What did we find out?

“Welcome me Estonia” was not an exhibition that offered much information about the asylum seekers of Vao. The method of this exhibition is not activist documentalism, which aims to create visibility for marginalized social subjects. On the contrary, the exhibition emerged from the time spent in the art classes, of which various material objects remind us, including handicraft items and commodities produced from recycled materials. There is some artistic experimentation with different techniques, such as collage and video. Some art objects have been produced from the joy of experimenting, while other works are more ambitious, encoded with a socio-critical message.

The aesthetics of the exhibition reveals the manner in which the committee for “LadyFest” has instructed the art classes before the exhibition. It was a humble pedagogy based on doing things together, getting to know each other and mutual listening. One can imagine that in the background of these activities many interesting dialogues and affective relationships developed, and perhaps even some subject positions changed between the participants of the art classes. This, in turn, refers to the fact that framing the “LadyFest” exhibition only as an art project would be reductive.

In conclusion, it can be said that the exhibition “Welcome me Estonia” was born out of a process that was simultaneously rooted in the contexts of activist solidarity work, feminist pedagogy and contemporary art. The methods derived from these contexts partially overlap and reinforce each other, so that they are difficult to distinguish analytically. However, at times, these strategies are also incoherent with each other, producing power dynamics that are complex and controversial. In this sense, the “LadyFest” exhibition project and related processes can be conceptualised as an experiment, the success and failure of which offer something valuable that activists, feminists as well as artists can learn from.

Airi Triisberg is a writing, curating and organizing art worker from Tallinn.

1 Redi Koobak, Millest me räägime, kui me räägime feminismist Eestis? – Ariadne Lõng 2015, no 1/2, pp 49–69.

2 Claire Bishop, The Social Turn: Collaborations and Its Discontents. – Artforum International, Vol 44, Issue 6 (February), pp 178–183.

3 Mari Peegel, Festival LadyFest annab varjupaigataotlejatele hääle. – Eesti Päevaleht 9. III 2016.