14. VI–6. X 2013

Kumu Art Museum

When Irving Penn (1917–2009) donated one hundred photographs to the Moderna Museet in 1995 in memory of his Swedish-born wife and model Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn, it became one of the largest collections of Penn’s work outside the US. The exhibition “Irving Penn – Diverse Worlds” organized by Kumu in cooperation with the Moderna Museet includes about ninety photographs from those donated and those already part of the museum collection. According to the curator, Andreas Nilsson, the selection introduces the breadth of Irving Penn’s work and shows Penn’s studio as a meeting point of various themes. The exhibition covers more than fifty years of Penn’s seventy-year career. All of Penn’s most important photographic series and themes are represented here with at least a few photographs. Depending on how you look at it, the exhibition can be seen as a unique mini retrospective or an introduction to the work of one of the most original photographers of the 20th century.

Irving Penn, who dreamt of becoming a painter, studied under Alexey Brodovitch, a Bauhaus-minded Russian immigrant. Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Garry Winogrand and Lisette Model can all be considered to a lesser or greater extent his students. All these names spring to mind when looking at Penn’s work in the exhibition hall. It is not only about the era or the location, but also the ability to focus, the mastery and constructive self-criticism that unites those photographers. The high demands they set themselves is the reason Penn never became a painter—washed clean of the paint, the canvas was used as a tablecloth in Penn’s home.

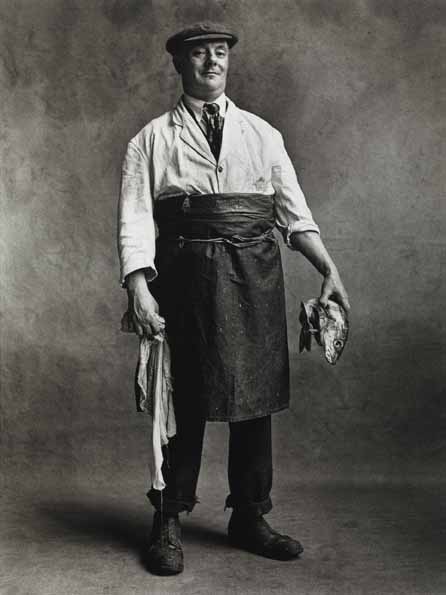

In 1943, Irving Penn was invited to work for the art department at Vogue. The photographers there were not very enthusiastic about the cover ideas that art director Alexander Liberman had for the magazine, and that is why he asked Penn to produce them. During their collaboration, which lasted sixty years, Penn photographed two hundred Vogue covers plus advertisements, still lifes and portraits. True, Vogue was a different magazine back then; it financed Penn’s largest photographic series, “Small Trades”, depicting skilled and menial workers, and published his series on exotic cultures produced during his numerous travels.

Irving Penn

Fishmonger, London

1950, negative

Courtesy of Moderna Museet,

Condé Nast Publications

Penn certainly had a new approach to fashion photography. He photographed models bereft of their usual environment and experimented with form and composition more freely than many others. In the early 1950s, they wanted to substantially reduce Penn’s work load at Vogue because the editors thought his work was too extreme for the magazine. With a brutality that was characteristic of Penn he admitted that1 he then understood what was expected of him as a fashion photographer – clean, sweet pictures of lovely women – and from then on he tried to produce commodity instead of photographs. This is a bit ironic coming from a man whose fashion photographs ended up in the collections of various art museums. Instead, Penn demonstrated that the presumption that commodity would automatically signify low quality is a sign of our own limitations and unpretentiousness.

Irving Penn’s portraits have a signature style that cannot be mistaken for anyone else’s. He took photographs of models in his studio on a simple monochrome background, on a base built from pieces of furniture or covered with carpet, or placed them in a corner built in the studio. The latter created a unique intimate space where, depending on the models, they could feel extremely comfortable or insecure. Later, extremely large close-ups replaced these sets and the nature of the person was therein realized through the relationship between the photographer and his subject, whether reflected in an expression, gaze or a hand concealing the subject’s eyes.

By portraying many of the celebrities of the 20th century, Penn knew very well the price they had to pay for their fame. Although he avoided publicity in every way he could, Penn soon discovered himself in the same position. Fame changed the relationship between him and his subjects and made his work as a photographer more difficult. Penn has said that2 models tried to be more seductive before the lens of a famous photographer, and using their charm they hope to convince the photographer to depict them as even more attractive. This was especially true with Penn, as everybody knew that Penn did not consider “attraction” and “beauty” to be relevant in portraits. Portrait photography for him meant reaching beyond the facade. Penn has compared portrait photography to surgery3 and the camera to a scalpel. These comparisons are well suited when we think that his studio in Manhattan with its light grey walls and dirty windows was referred to as “the hospital”.

One of the most interesting groups of photographs from Penn’s camera in the Kumu exhibition are the portraits of local people photographed in portable tent studios during his travels in Morocco, New-Guinea and Dahomey. These works have often been seen to parallel Penn’s fashion photography, which are viewed as aesthetic constructions. Now, when many of those indigenous people have lost their traditions, we cannot underestimate the historic ethnographic value of Penn’s work.

Penn’s still lifes, nudes and close-ups of items found on the streets paint a picture of the lives of his models behind the camera. Not by judging but confirming once again that every thing in this world is worth looking at with understanding.

On one hand, Irving Penn’s exhibition could be seen as a portrait of a 20th century American – the pictures published in Vogue offer a pretty good idea of what haunted and excited the reader. On the other hand, Penn’s work provides food for thought at the beginning of the new century when time and quality have become luxuries.

Hedi Rosma is the Estonian editor for KUNST.EE.

1 Vicki Goldberg, Irving Penn is Difficult. “Can’t You Tell?” – The New York Times 24. XI 1991.

2 Ibid.

3 Irving Penn. – Photography Annual 1966.